Half-decade, multitrillion-dollar Dixie Road overpass redo to comfortably accommodate additional lane of QEW gridlock

- G Papa Tango

- Aug 8, 2025

- 5 min read

In a bid to alleviate the perennial gridlock on the Queen Elizabeth Way (QEW), authorities have embarked on an ambitious project to overhaul the Dixie Road overpass. This endeavor, slated to span half a decade and cost multitrillion dollars, aims to not only address existing traffic woes but also to future-proof the infrastructure against burgeoning demands.

The QEW, a vital artery of Ontario's transportation network, has long been plagued by congestion, especially during peak hours. As urbanization continues to swell populations in surrounding areas, the strain on this crucial thoroughfare has only intensified. Recognizing the imperative for action, authorities have directed their focus towards the Dixie Road overpass, a notorious bottleneck contributing to the snarl-up.

The overhaul, set to be one of the most extensive transportation projects in recent memory, will see the expansion of the overpass to accommodate an additional lane. This strategic augmentation is poised to enhance traffic flow and reduce the likelihood of bottlenecks, offering commuters a smoother journey and businesses more efficient logistics.

However, the scope of the project extends beyond mere lane expansion. Engineers and planners are integrating cutting-edge technologies and sustainable design principles to ensure the revamped overpass aligns with modern transportation needs. From advanced traffic management systems to eco-friendly materials, every aspect is meticulously curated to maximize efficiency while minimizing environmental impact.

Yet, such a transformative endeavor does not come without challenges. Disruptions to daily commutes, logistical complexities, and environmental concerns loom large. Moreover, the substantial financial investment required underscores the gravity of the undertaking, necessitating prudent fiscal management and transparent accountability.

Nevertheless, the long-term benefits promise to outweigh these hurdles. A smoother-flowing QEW means reduced commute times, enhanced safety, and bolstered economic productivity. The Dixie Road overpass revamp symbolizes not only a commitment to addressing immediate congestion but also a forward-looking approach to infrastructure development.

As construction commences and progresses over the coming years, stakeholders—commuters, businesses, and residents alike—will undoubtedly experience the impacts, both positive and challenging. Yet, amidst the inconvenience and upheaval, lies the promise of a more efficient, resilient, and interconnected transportation network, propelling Ontario towards a brighter future.

FURTHERMOREOVERKILL

G Papa Tango, know anything interesting about the history of the overpass?

Ooh, which overpass are we talking about? There are a few around that have some quirky or poignant stories—whether it's a local spot like the footbridge over the QEW in Applewood or a big-name one like the Gardiner Expressway ramps. If you can tell me the location or even just the general area, I’ll dig up something good.

No, generally speaking, the thing that is the overpass.

Ah, got it—you mean the concept of the overpass itself. That’s a surprisingly rich topic!

At its core, the overpass is just a bridge—a structure that lets one road pass over another—but its history and symbolism go way beyond concrete and rebar.

A few interesting things about overpasses:

1. Born of the car age

Overpasses became widespread in the early 20th century, especially in the U.S., as cars took over and the dream of smooth, uninterrupted driving became an obsession. They’re the backbone of the interchange—a kind of road choreography meant to keep traffic flowing without stops. Think of cloverleafs, flyovers, spaghetti junctions—they're all part of this post-war highway utopia idea.

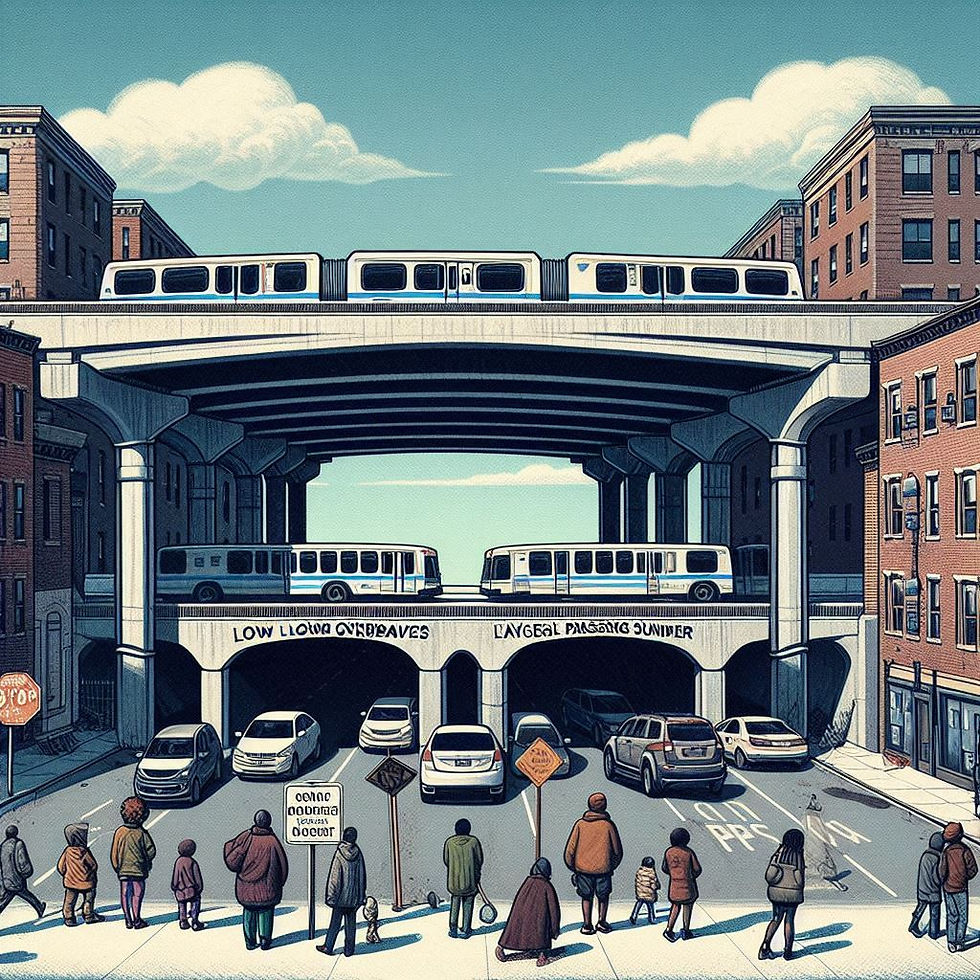

2. A symbol of modernity—and inequality

Overpasses were often touted as marvels of modern engineering. But they also became symbols of urban segregation. In cities like New York, planner Robert Moses allegedly designed overpasses low enough to block buses, preventing lower-income people (often racialized groups) from easily accessing certain areas like beach parks. Whether that was intentional or not is still debated, but the effect was real.

3. Ruins in waiting

Many overpasses built in the ‘50s–‘70s were made with a 50-year lifespan. Today, some cities are dealing with crumbling infrastructure, leading to dramatic removals or re-imaginings—like the Gardiner in Toronto or the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco, which was torn down after an earthquake and led to a complete rethinking of urban space.

4. Reclaimed as art and space

Some cities have turned underpasses and overpasses into something beautiful or useful. Underpass parks, pop-up skate parks, murals—these gray zones are getting new life. Toronto’s Underpass Park under the Eastern Avenue overpass is a great example: concrete columns turned into canvases, and barren lots turned into playgrounds and basketball courts.

5. They echo in culture

The overpass shows up everywhere in film and fiction—as a space of transition, danger, or isolation. Think of chase scenes, graffiti, tragic encounters, or lonely moments. They’re often liminal zones—not quite here, not quite there.

Want more on one of those threads—like the Robert Moses story or the Underpass Park revival?

Sure, please.

Let’s go a little deeper into both—the Robert Moses story and Toronto’s Underpass Park—because they weirdly mirror each other across time.

🧱 The Robert Moses Overpass Controversy

Robert Moses was an urban planner in New York during the mid-20th century. The guy reshaped the city with bridges, highways, parks—and a whole lot of concrete. He was visionary, powerful, and famously unaccountable to the public. One of the most enduring legends about him involves overpasses on Long Island's Southern State Parkway.

According to urbanist Robert Caro’s 1974 biography The Power Broker, Moses designed some of those overpasses deliberately low—around 7 feet—too low for buses to pass under. The idea was to prevent poor and racialized New Yorkers, who relied on public transit, from easily reaching Jones Beach, which was meant for car-owning suburbanites.

Caro’s book ignited debate, but modern historians are split: was it truly an intentional act of class and race-based exclusion, or just a technical quirk of the time? Regardless, the legacy is clear—infrastructure can act like policy, even when it doesn’t look like it.

🎨 Toronto’s Underpass Park: Turning It Around

Now flip the narrative.

Toronto’s Underpass Park, tucked under Eastern Avenue near Corktown and the Don River, takes that dark, dead space beneath an overpass and turns it into something vibrant. Launched in 2012 as part of the city’s West Don Lands revitalization, it includes:

Basketball courts

Playgrounds

Skateboarding features

And a huge amount of public art

It was part of a push to humanize city infrastructure, especially in a formerly industrial area that’s now home to new condos, green spaces, and bike paths. What used to be gritty and forgotten is now a hub of energy, especially for kids and artists.

The overpass becomes a roof, not a wall—sheltering people rather than separating them.

There’s something poetic about that: the same type of structure used in one era to divide, reimagined in another to unite and inspire.

.png)

Comments